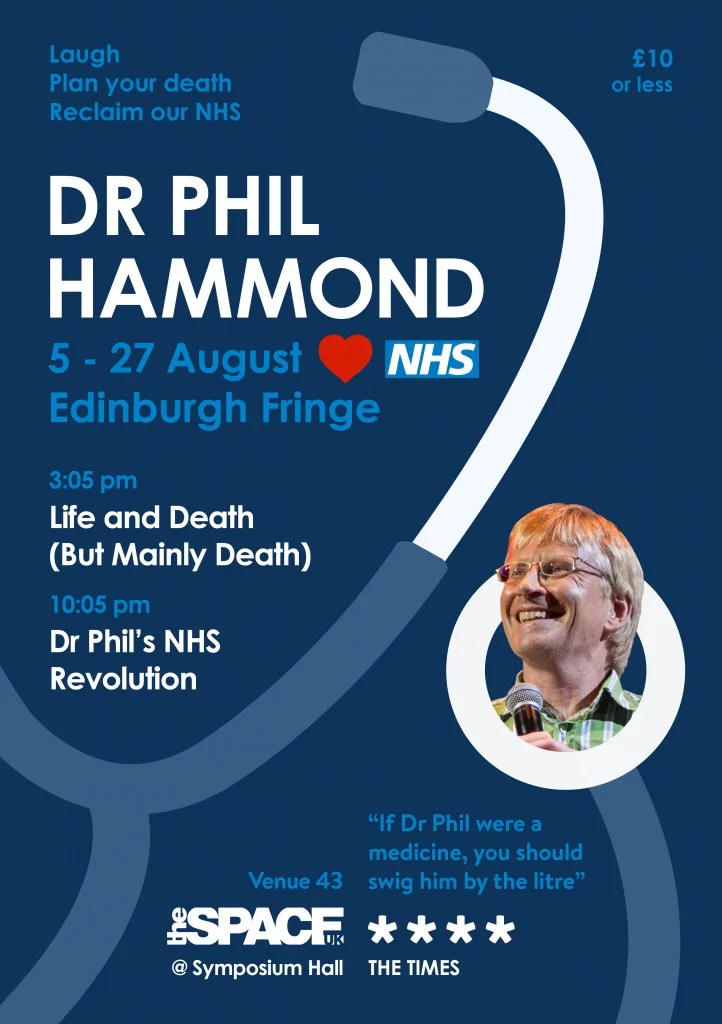

Dr Phil Hammond's 50-minute show Life and Death (But Mainly Death) should be tougher going, given that he's talking to us – as advertised – mainly about death. He even opens the show by telling us that people who see shows with "death" in the title are statistically more likely to die.

We're led into the death discussion via a powerpoint presentation about Dr Phil's family history, illustrated with some fascinatingly goofy pictures of the man himself. In a sharp steer into the tragic, we learn of the death of his father at age 38, which his mother told him was a heart attack. After training as a doctor in the NHS and writing for Private Eye, he found out his father's death was actually suicide.

"We either get cancer, heart disease or stroke. That's how we die in this country. Get used to it."

Frank death talk it truly is, yet somehow both the show and my subsequent conversation with Dr Phil feel comforting – perhaps dying is actually normal, and not something we're supposed to rage, rage against after all. Given that we're in the midst of a death festival within a festival and conversations about death are becoming more commonplace, are we perhaps becoming more accepting of dying?

"I think we’re sort of becoming more accepting of it," says Dr Phil, "I say that maybe we actually did it better in the old days – I can remember as a junior doctor, a nurse would come to you at the end of the day and say 'Can you sign up these drugs for these patients?' and then the patients would die overnight, nearly always when there was nobody around, and they’d have decent, kind, gentle deaths. I guess one of the side effects of advances in technology in medicine is we have the capacity to pull out all the stops, and give people high-tech deaths that are actually quite unkind. Just because we can do something doesn’t mean we should."

Fear of death has increased as belief in god has waned, but is that the reason or is it just incidental? Dr Phil thinks it might be moving life and death out of the home. "The anthropological bookends of life, birth and death, used to happen in the home and therefore we weren’t frightened of them. People used to lay the bodies out, they wouldn’t call the undertaker immediately, the whole family would be there, the kids would be playing at the person’s feet. The fact is that now most of it, too much of it, happens in a hospital. It takes it away from our cultural experience and that makes us frightened of it."

It's often said that the NHS is our national religion, which makes doctors the unfortunate deities whom we turn to for answer and salvation. Yet when doctors themselves talk about their own deaths, the "pull-out-all-the-stops-to-save-me" approach isn't what most of them want. "If you look at what doctors would want when they’re dying, they want virtually no intervention at all. They don’t want dialysis or resuscitation, they just want to be kept comfortable."

In a much softer manner than he announced during his show, Dr Phil tells me how I, and indeed he, will probably die. "If we don’t kill ourselves, generally we are going to die of cancer, heart disease or stroke. Those are the normal ways of dying." Well, I guess we're all friends here now - so which would he go for, given the choice? "I think I’d like to go quickly. Probably a heart attack. Quick, boom – and not be resuscitated." Why are doctors so down on resuscitation? It works BRILLIANTLY in the movies and on TV, a few shouts of "Clear!" a shock or two and they spring back to life. Except it doesn't happen like that. If you have a heart attack outside of a hospital, you have around a 6 or 7% chance of survival, according to Dr Phil. "Things like ER and Casualty show lots of successful resuscitations, but actually resuscitation isn’t usually successful because it generally happens to older people. When your heart stops, it’s generally telling you something. Young people who have cardiac arrest are worth resuscitating for a long time – there are rarities like that footballer, Fabrice Muamba, who was 23 and very fit and athletic – but once you get older your chances of survival are pretty poor."

Dr Phil spent much of his young life believing his father had died of a heart attack at 38, and several times during he show he says, "...and I thought, 'Well I might as well do it, I'm going to be dead at 38.'" So was finding out his father killed himself a relief, in a way? "Well, I didn’t want a genetic predisposition to a rare condition that makes your heart stop, but if you have severe depression and suicide in your family it gives you a 40% increased risk. But I’m not my dad, I’ve learned. By the time I found out about my dad I’d done lots of stressful things and never suffered any mental illness and I don’t think I ever will. I’m very lucky. So in a way it was a relief."

So what can we take away from all these death discussions? Should we all just bloody well accept that we're "leaves on the death tree" and get on with it? Well, yes, but there's no need to be a dick about it. Dr Phil's comedy partner, Fresh Meat star Tony Gardner, used to break the news of a cancer diagnosis by saying, "You know what your problem is? You've got cancer and you're going to die." He said occasionally patients would admire his honesty and frankness, but others would be very upset. "I think a bit of honesty is important," says Dr Phil, "but kind truth is what we need, not brutal honesty."

If anything, what we should take away is a plan for our own deaths, or at least the courage to talk about it. "Some people do plan it and think about it and some people don’t, but if you don’t you’re risking having an unpleasant and over-technical death. So I think the message is, it’s never too late to talk about things, and talk about your wishes with your family and what you want, commit it to paper and plan it."